A Park with a Rich and Complex History

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

To make a significant move towards the future, we must first recognize the significance of our past: the history, the people, our homes and the land on which they were built — all culminating into what stands before us today.

We are working to capture and share the unique history and story of Central Village Park. If you would like to share your memories of the park and its development, please contact us. And if you have photos of the neighborhood prior to, during, or shortly after the development the park, we would love to see them!

In the 1950s, efforts began to connect America’s cities with endless roadways – the Interstate system. Connecting the downtowns of St. Paul and Minneapolis, a path was charted for Interstate 94. Despite other available and less intrusive routes, transportation planners of the day chose a route that would run right through the Rondo, the heart of St. Paul’s Black community.

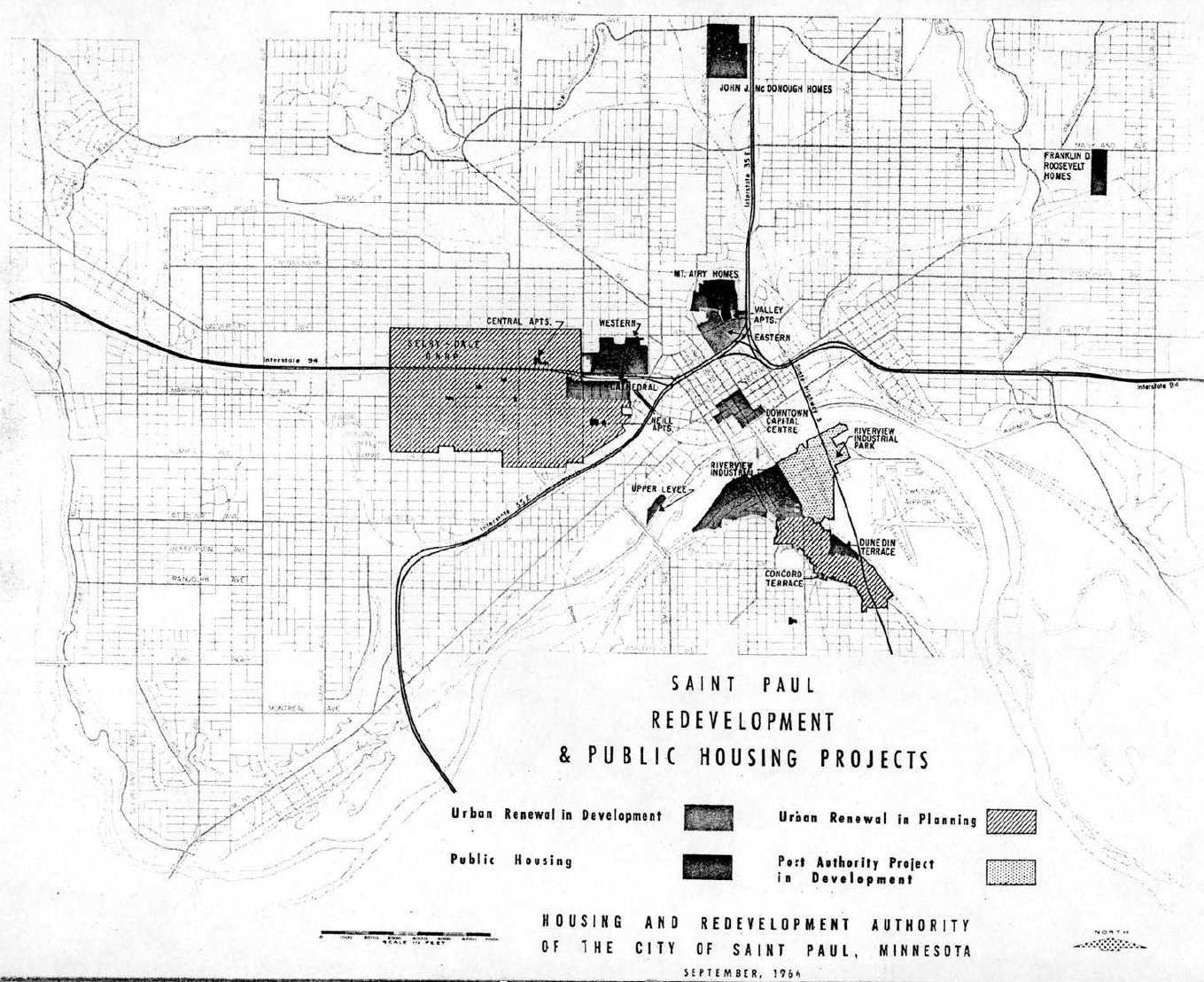

Some civic leaders at the time viewed the improvements as a way to expand mobility and economic growth while spurring redevelopment and doing so in a manner that was politically expedient given the disregard for the Black community. The condition of the area’s housing – some of which was behind the times and lacked modern amenities – was used as justification for the “blight removal.” This legally justified the construction of the freeway and destruction of the commercial corridor along Rondo Avenue and many of the residential buildings in the area.

In the 1970s, plans for “rebirth” of the residential and commercial areas began alongside planning of the freeway, although redevelopment took longer to occur. Known as Project UR Minn. 1-2, the redevelopment area encompassed a total of 78 acres spanning from the State Capitol to Dale Street. Plans called for public amenities, including a school, park, and greenway. Planners acknowledged limited parks and open space, writing, “The entire community needs a recreational park, the nearest such park, Dunning Field, is over two miles away.”

After several proposals the decision to demolish the existing housing stock and create suburban style living was approved. The new proposal included housing with larger lots, attached garages, and col-de- sacs. This change brought on another wave of disenfranchisement in the Rondo community. Over 10,000 Individuals including generational families of seniors, adults and children were forced to move. For some families this was doubly punitive because they were displaced from Rondo Avenue and for a second time were being displaced again. Now see where we’ve come.

And that is how Central Village Park was born. But it is story is still being written.

While many of the historic businesses, homes, and social connections were destroyed or impacted, the commitment of neighborhood leaders never waned. Central Village Park is a story of people. The people who created change, celebrated culture, and connected neighbors. And sometimes the people with conflicting ideas for the future of the neighborhood. Central Village Park is the story of Bobby Hickman, Camilita Harris, David Vassar Taylor, Debbie Montgomery, Dick Mangram, Donald Walker, Rev. James Battle, James Milsap, Jim Mann, Dr. Jim Shelton, Kate Cavett, Mark Bastian, Melvin Carter, Nadine Bergstrom, Roger Anderson, Rosie Lee Butler, Stella Whitney, Toni Carter, Willie Mae Wison.

Central Village Park is a story of organizations. The organizations that advocated for the neighborhood’s best interests, provided places to gather and recreate, and remained as legacy neighborhood institutions despite upheaval and change. Central Village Park is the story of Hallie Q. Brown, Mount Olivet, Camphor, Martin Luther King Neighborhood Center, Aurora-St. Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation, Control Data, Model Cities Inc, Urban League, and Penumbra Theatre.